Goodbye to most of the daydreams.

Float, fan, tissue, blutack, string, cutout, 2008

First Ice, 09’09, 2008

Cyclorama,15’37”, 2008

COLINE MILLIARD - Alex Pearl, Impressions of Antarctica

When I dream about eating: as I bite into the apple, donut, whatever, there is always nothing there. I've always wanted to make art like that. Alex Pearl

It’s official: Alex Pearl did not travel to the Antarctic. His application not to go was accepted by the British Antarctic Survey in June 2008, and he dedicated most of the following year to documenting his non-journey to the pole. Throughout his residency at BCA Gallery, the artist echoed the voyage of the great adventurer Robert Falcon Scott – famous for reaching the South Pole thirty-four days after his Norwegian counterpart Amundsen – without leaving his studio, unhampered by the inconvenience of actual travelling. With texts, videos, drawings and sculptures, Pearl developed in the exhibition ‘Goodbye to most of the daydreams’ a poetic meditation on the faraway and the means by which we access it.

Like Scott, the artist kept a diary, a blog in fact – later turned into the limited-edition book Journal (all works 2008) – but instead of progress into the unknown land or the tally of dwindling supplies, Pearl detailed his weekly commuting between Ipswich and Bedford, his short trips to London, and all the ups and downs of his daily life. It sounds like a non-story, but Pearl’s trepidation and excitement turns these quotidian activities into a succession of explorations, directly confronting the notion of ‘adventure’ and where it is to be found. This chronicle, like those of most explorers, is accompanied by sketches. Everyday the Antarctic Survey puts up on their website a new photo from the Pole, the images ranging from scientific to downright cute. Pearl patiently retraced these pictures, safely appropriating the activities and risks taken by others. ‘These drawings are about definitely not being there’, he says. ‘They are leaching off other people’s experiences.’ Under Pearl’s pen, these images of polar exotica take on a new identity, an ice crevasse becomes a tangle of biro strokes, wilderness is domesticated.

Neither the series of drawings nor Journal is Pearl’s first experiment in diary-keeping. The artist is an inveterate blogger, compulsively recording and divulging his daily activities on the net. Sometimes, as here and in Pearl’s 2007 project at the Foundling Museum, an artwork or an artist’s book comes out of this routine, but it is mostly a web-wide sharing of his existence, artistic anguishes and self-doubts. Blogging is also an immediate form of storytelling, and throughout his blogs, Pearl has developed a multifarious and likable persona: the angst-ridden artist, the universal anti-hero who misses trains and energetically procrastinates. Even if strongly autobiographical, it is unclear how many of these entries are genuine. Alex Pearl could be playing ‘Alex Pearl’, his web alter-ego, but this ambiguousness only enhances the character’s appeal.

Pearl’s use of the internet expands far beyond the blogosphere: all his videos are available on Youtube, and most of his other artworks are meticulously documented and easily reachable online. ‘I like the way the internet is very unmediated’, Pearl says. The web allows him to put his work, like his life, out there, without any selection, perhaps to see how it is received. This isn’t always a positive experience; Pearl has made a cringingly funny book, Feedback (2006), of the insults he gets on Youtube. The web’s openness is mirrored in Pearl’s practice by a knowing sense of accessibility. ‘I don’t like the idea of being too clever or difficult’, says the artist; instead he advocates immediate reception and enjoyment. In Float, for example, a puny ship silhouette bravely sails a raging ocean made of tissue paper blown by an outdated fan. Delightfully illustrating the power of make-believe, Float’s success lies precisely in its disarming simplicity.

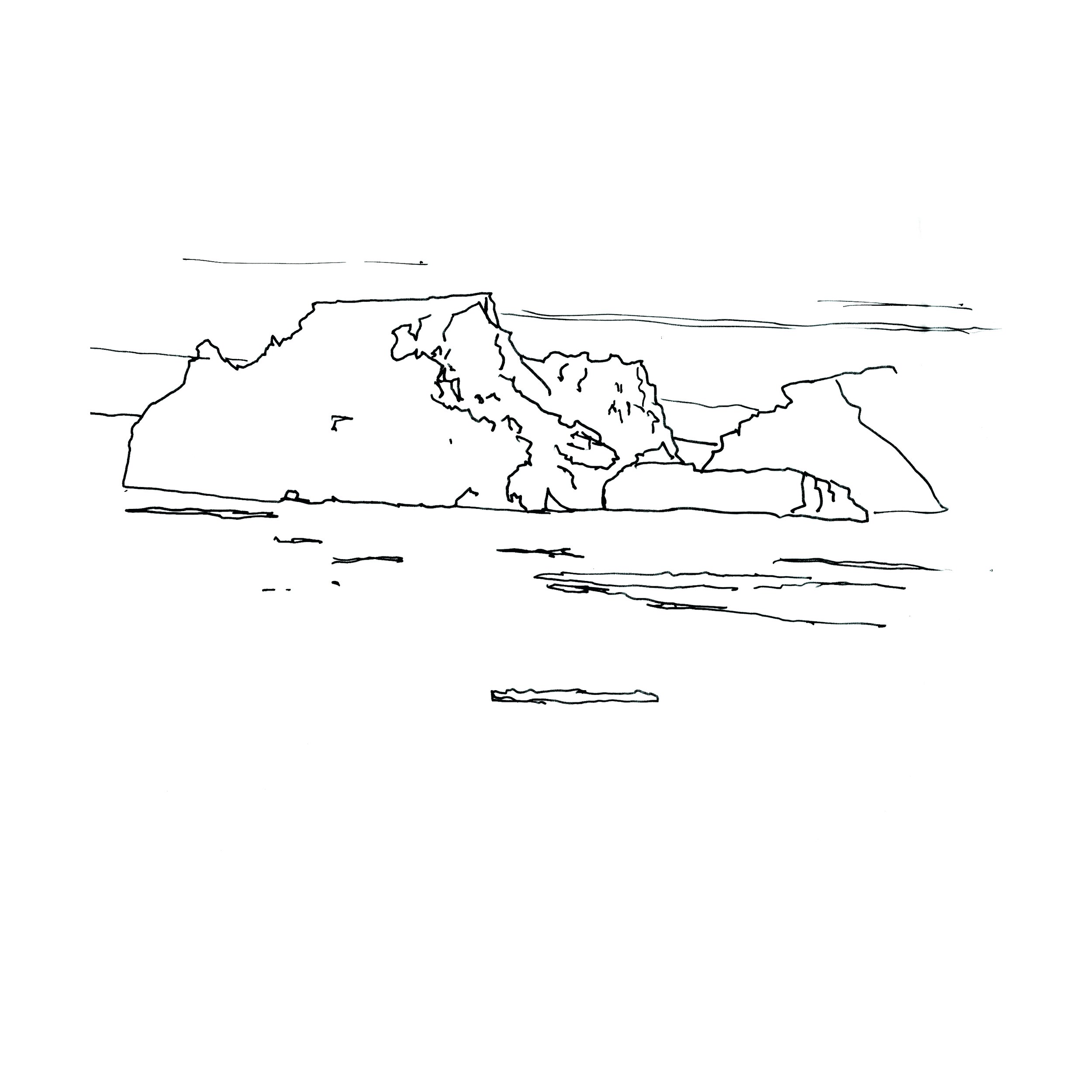

Float also bears the pungent whiff of nostalgia, embodying the artist’s desire to go back to a certain childlike frame of mind, where everything is possible as long as you do it yourself – a hands-on attitude at the core of Pearl’s practice. Improvisation is his only strategy, and his materials are available in every household; the excitement lies in the putting-together process. ‘It’s like an adventure or being exploratory’, says the artist of his working method. ‘It’s also like being a kid. When you are a child and you want to do a robot, you don’t go to robot school first, you just make it.’ Just as Raymond Roussel dreamt up his Impressions of Africa (1909) in the comfort of his Parisian home, Pearl constructed his own South Pole in his Bedford studio, and the video First Ice narrates the voyage. Seen like through the lens of a telescope (actually a sink hole), ice cubes become icebergs, polystyrene beads a snowdrift, bed sheets an immense white land. At times the image is blurry, documentary-style, daring the viewer to believe for a second that this could really be an underwater shot from Antarctica. But obviously fake elements keep unsettling the illusion, occasionally – as in the case of a bunch of pink plastic flamingos – creating a clash of exoticisms undermining the notion of a desirable ‘far-flung’.

In Roussel’s proto-surrealist book, the narrator (allegedly) first encounters the African coast through his telescope. This circular viewpoint provides a leitmotiv for Pearl’s ‘Goodbye to most of the daydreams’ series, encapsulating distance and otherness, what is both feared and craved for. In the collages of Untitled, Found Ships, boat pictures are seen through the lens of LP sleeves holes; in the poignant video Eva, a little vessel is followed by some invisible observer’s spyglass. But it’s in Cyclorama that this remote point of view is most powerfully summoned, even it doesn’t involve any disc-like perspective. Sitting on top of an ironing board, a strip of paper uncoils between two spools, unraveling a frozen landscape seemingly seen from afar. A single horizon line gradually turns into an iceberg, a penguin, a cross, the sea. It’s a compilation of clichés, depicting the South Pole like in an automatic drawing – and yet here it is, this fantastical Antarctica, genuinely unfolding before our very eyes. ‘It’s like magic’, says Pearl, ‘if a magician says something is happening it becomes real.’ That’s all it takes to travel.